[Play Arendarvon Castle online] [backup]

In previous posts, I wrote about Wander (1974), the interactive fiction creation tool for mainframe Unix systems. But my speciality (I use the word laughably) is text adventure games for the BBC Micro, the legendary 8-bit microcomputer that helped kickstart the 1980s home-computing revolution in the UK. (The story of its creation has been immortalised on film.)

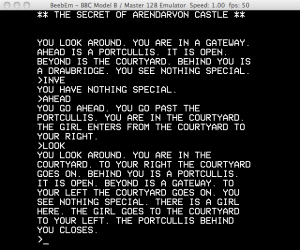

The Secret of Arendarvon Castle by Arend Rensink is a text adventure game that was written not just for the BBC Micro but also for the Sinclair Spectrum, the Apple II, the Commodore 64, and the IBM PC. The game was notable for several reasons.

Bytecode

Firstly, the fact that there were versions for so many different systems can be explained in part by the way that the game was implemented — as a sort of bytecode. The bytecode ran on a small virtual machine, and there was a different version of the virtual machine for each of the home computers that the game was released for.

If you know about Infocom’s virtual Z-machine then you’ll find the concept familiar, but, as the author Arend Rensink told me after I asked him about the similarity, his own bytecode, ALADIN, was an independent invention:

It was independent; in fact, this is the first time I’ve heard of the Z-machine at all. Yes, I agree that it looks like essentially the same idea, and clearly they [Infocom] were there before. Well, in my defense I can claim that literature research was somewhat more cumbersome back then…

The idea of portable bytecode was a good one, but, in practice, it seems not to have worked out exactly as intended:

… the encrypted [data, much of which] is … a kind of bytecode avant la lettre … is … different from one computer to the next. That’s really a pity, for it means that your work will not be reusable [on machines other than the BBC Micro]. I suspect it might have something to do with memory layout differences, but I do not remember …

Type-ins

The “work” that Arend mentions is my cue to talk about the form in which Arendarvon Castle was distributed. As wasn’t uncommon in the 1980s, the game was published in the form of a BASIC program listing in a book, which you were supposed to type in by hand.

Yes, that’s right. You were meant to spend hours painstakingly typing and checking and re-checking and cursing and crying your way through the listing till every single line — sometimes hundreds of them — and every single command, string, and colon had been entered into your computer in exactly the same way that it had been printed in the book. And even then, when you were absolutely sure you had corrected your every last typo, the program often wouldn’t work because there had been a printing or typesetting error that hadn’t been caught before the book went to press.

Checksums

Although there was no way to guarantee that a listing would be free of printing errors, Arend Rensink came up with one innovation for Arendarvon Castle that at least made it easier to spot when you yourself had made a mistake: checksums. The book included a program that would detect whether the bytecode that you’d typed in, which appears in the listing as long sequences of unintelligible numbers and letters, had an error in it. This was a godsend, which saved you a lot of time and bug-hunting eye-strain, and I can personally attest to that because I used the checksum program when I and another willing scapegoat recently sat down to input the listing into a BBC Micro emulator.

Thankfully, we weren’t typing everything in by hand. Arend had already put scans of his whole book online, including the listings, and it was those scans that we initially tried to go by. But they soon proved to be of too low a resolution to be useable. So I contacted Arend and told him of our plight, and he very kindly supplied higher-quality scans of the listings, and even OCRed them for us. The OCRing wasn’t perfect, but it was a start, and, with the help of the checksumming system, the game was soon up and running in BeebEm.

The game we typed in can now be played online [backup]. As far as I know, this is the first time The Secret of Arendarvon Castle has been put online in English. (The game and the book were also published in German and Dutch.)

Where am I?

The game is unusual for a text adventure because the player doesn’t use compass directions to navigate her way through the locations in the game, but instead uses the commands LEFT, RIGHT, AHEAD and BACK. So you have to keep reorienting yourself whenever you enter a room.

In a conventional text adventure in which you move by going NORTH, SOUTH, EAST and WEST, you can usually go from, say, the South Chamber to the North Chamber by walking north, and then return to the South Chamber by going south. In Arendarvon Castle, you’d make the same round-trip by going AHEAD and then BACK but, on your return, all the exits from the South Chamber would effectively be “reversed”, so that whatever was RIGHT before you left the South Chamber will now be LEFT, and vice versa.

This makes for tricky gameplay, although you’d probably get used to it in time. I haven’t had the chance to find out, though, because I always seem to be on the hunt for new old games, and forever distracted from actually sitting down to play any of the ones I’ve already found!

Artwork

But perhaps Jason will add this one to his list of All The Adventures that he’s been playing his way through. If so, he’d be well advised to download the scans of the book that Arend Rensink intended the player to consult frequently while playing the game, because they contain a lot of supplementary — and in fact essential — material that you’ll need if you want to discover all the castle’s secrets.

The stories, journal entries, mock newspaper clippings and other documents in the book are the last — but not the least important — reason that The Secret of Arendarvon Castle is a noteworthy entry into the canon of classic text adventure games. The book is lavishly illustrated, by Bert Vanderveen, and the pictures, together with the detail in the accompanying text, conjure up an atmosphere full of occult intrigue that would surely have enticed many[1] a home micro user in the 1980s to take the plunge and start typing in those lines and lines of source code, one character at a time.

More details about The Secret of Arendarvon Castle, particularly its authorship, can be found here at CASA, the Classic Adventure Solutions Archive.

A disc image of the game suitable for loading into BeebEm, the BBC Micro emulator, is available here [backup].

UPDATE, January 2020: Some time ago (in 2015!), Bert Venderveen, who designed and illustrated the book, emailed me with some interesting background info:

Thirty years ago, sigh. I did not only (partly) illustrate that book, but also designed it, made the clippings etcetera. Was great fun, but I don’t remember much about that time. Just that Arend was a brilliant young man (18, I think at the time), whose father happened to be the toughest (and best) teacher I ever had in middle school (coincidence!).

The so called lead authors (Alex and Kasper) were also clients of mine in other fields. Alex had a software firm (Omikron) — I did a corporate identity for them and brochures and stuff like that — and Kasper became involved with the Dutch Open University and had me illustrate a few books there. He also bought a sporting goods store in Eindhoven, if I remember correctly — mostly as something to keep his son(s) on the straight and narrow. I think I did a logo for that.

I had a look at the scans of the book and was amazed about the amount of work that went into it. Mind you: the Mac was not a tool for designers then, everything was done by hand. I remember I had a load of basic layout-grids printed in non-repro blue on special coated paper stock, which make paste up a lot easier and faster. The code in the back was supplied to me in the form of matrix print out, which I divided into page lengths and slightly reduced on a photocopier before pasting them into the layouts.

The publisher (Addison-Wesley) did the conversions into German, I believe. They mashed up my cover design and used terrible lettering, really eighties’ style ; )

I had help from some friend/illustrators: Betty van Spijker (who is my neighbor now) and Wieger Slothouber, a great guy (in all respects, he was over 2 meters tall), who sadly passed away about fifteen years ago. Betty’s work is the more dreamy and soft, while Wieger was a master of dramatic shading and penwork. I did a lot of the semi-realistic stuff in airbrush and the cartoony/comic illustrations. And all the handwriting. I still own the fountain pen that is in the photo’s used in the character openings. I did the photography as well.

Well, thank you […] for sending me back to memory lane!

Feel free to add my info to your blog. I think it is amazing that folks play that game thirty years after it was published!

Many thanks for your insight into the making of Arendarvon, Bert!

[1] I say “many”, but in fact it’s not clear exactly how many copies of Arendarvon were sold. In Arend’s own words, “It’s certainly never been a rainmaker ;-)”

The wizard on the cover made a bold choice dyeing just the beard white. Or is it the hair and eyebrows?

Maybe that’s the Secret?

Pingback: Wander follow-up | Retroactive Fiction

I’ll make sure I’ll get to it. Looks interesting!

I can tell you from Mystery Mansion: you never get used to relative position l/r/forward/back.

There’s at least one type-in coming up where it looks like I’m going to have to ACTUALLY TYPE IT IN.

I don’t envy you all the typing! If it’s possible to try OCRing the listings, do have a go. It’s *so* helpful. Correcting an OCR is much, much faster than typing code in from scratch — although part of the difficulty in the case of Arendarvon was that most of the code we were looking at wasn’t BASIC but machine code and bytecode encoded as random-looking alphanumeric characters. I think that typing BASIC in would probably be easier.

I typed the whole damn thing, back in 1984. I really enjoyed the challenge, actually.

Well done! Did you solve the game?

Is there any word on a link to playable version of the other Microworld Adventure by “Hal Renko,” The Antagonists? There seems to be a screen shot of the BBC version at CASA…

http://bbcmicro.co.uk/game.php?id=2032